Our fascination with wilderness pervades how we understand this land. Wilderness features in glossy landscape books, calendars and diaries, and encapsulates the essence of numerous outdoor clothing and equipment brands. It provides the scenic backdrop to advertisements and film sets, functions as an underlying value by which we market this country internationally as a tourism destination, and has been the stamping ground for a raft of iconic figures such as Charlie Douglas, Alice McKenzie, Ed Hillary and Rhys Buckingham. Indeed, wilderness is the driving ethos by which we now preserve and manage the majority of our most ecologically indigenous places.

And yet, while this way of imagining wilderness is often the prompt for self- congratulation at our collective foresight to set aside a third of this land as the public conservation estate, I want to argue that such contentedness significantly limits how we let our protected areas shape our sense of who we are in this land. For the way we have let these public conservation lands be conceptualised as a wilderness apart from people continues to entrench us as the perennial corruptors of ecologically indigenous New Zealand. Hence, for many, rather than appreciating the potential of people as intrinsic participants in the well-being of our unique places, we hold to a view that people must always remain outsiders. Such a position restricts the ways we allow this country’s deep history – that which is bound up in our endemic flora and fauna – to teach us more enduring, sustainable, and – given the unpredictable impacts of climate-change – resilient ways in which we could live here.

a non non-wilderness

Let me explain. Since starting work at a university, I have found it intriguing how academics understand wilderness. It’s been the subject of many studies that cover a myriad of issues, including perceptions of overcrowding, drivers for displacement, intrusiveness of aircraft noise, impacts of trampling, measurement of the economic benefits of conservation lands, and examinations of the ongoing tensions observed between the public, concessionaires and various governmental agencies. One set of studies, in which informants were asked to identify those factors that would affect their experience of wilderness, is particularly revealing.1 From their responses, those variables which were cumulatively deemed to detract from a wilderness experience – like the presence of developed campsites, commercial recreation, maintained tracks, bridges, huts, shelters and proximity of road access – were identified in several national parks. Then, with the aid of mapping techniques, spatial buffers of 1–4 kilometres were placed around each detracting feature, their size set according to the degree to which people considered these features would degrade wilderness. The researchers concluded that those remnant, unmarked areas were wilderness.

On one level, such an approach makes sense. It allows people to visualise how each additional track, hut or commercial activity could ‘diminish’ the ‘available supply’ of the ‘wilderness resource’. And yet the assumptions behind this approach are deeply flawed, and as such reveal how poorly as a nation we still imagine the place of people in our ecologically indigenous places.

For the wilderness these maps locate is not one determined by working out where wilderness is. Instead, wilderness as a physical place is the residue left from having identified where it is not. Similarly wilderness as a concept is not defined by what it is. Instead it is reduced to being the binary opposite of something else: in other words a non non-wilderness.

Such research confines wilderness to being those remnant places where the activities and artefacts of people are not. Its ‘pristine’ qualities – a word often used in wilderness writing – only come from it being untouched by people, remote from the places of people, other-worldly to culture. Consequently, wilderness is something people can only degrade, and which can only (partly) be restored through their removal. This is why we can readily articulate how wilderness is threatened and lost while still struggling to imagine ways in which it could be built up; we struggle especially to imagine how people and their activities could actually add to the quality and value of wilderness. It is this paucity in imagining what our place is within wilderness, and with it those places like our public conservation lands that are consistently associated with wilderness, that makes our current understanding of the term so limiting.

This notion that people have no plausible place in wilderness is not one purely of academic interest. As is discussed in the next section, it dominates the ways we image and interact with those places we label ‘wilderness’: in landscape photographs, tourism experiences, management strategies, outdoor equipment, track and hut design, and even such mundane things as track markers.

Keeping our distance

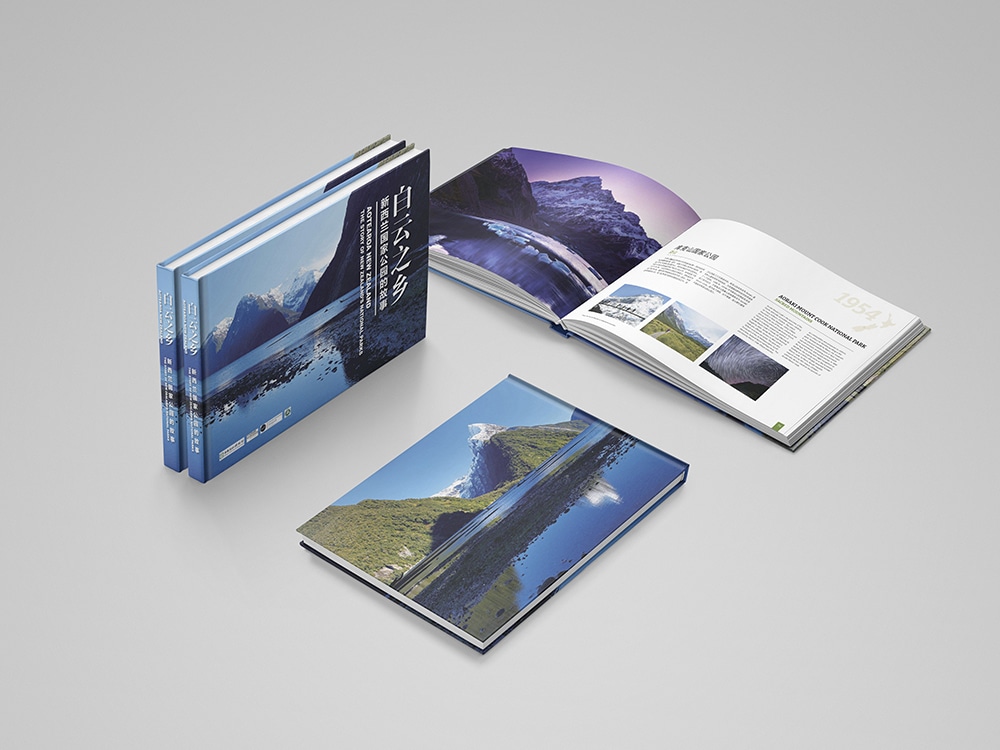

In the burgeoning genre of publications showcasing New Zealand’s wilderness landscapes, we are given the same picture. Image after image conveys an unspoilt scene rarely tarnished by the presence of people. And though this may be the enduring

picture we wish to hold of this country’s wilderness, such sentiments are of course illusory. For implicit in each image – if we allow ourselves to piece together what would be seen in the opposite direction – is a person shooing away sandflies, shifting wayward fern fronds away from the camera, firmly spiking the ground with a tripod, snacking on food as he or she waits for ‘the light to come right’, before finally packing up and leaving behind an assortment of marks made from equipment, boots and backsides.

This focus on wilderness as scenery is at the heart of New Zealand’s tourism marketing. From ‘100% Pure’ with its central pitch of a pristine Edenic land, to any number of tourism products, the same appeals pervade. Brian Turner conveys this sentiment in his Visitors Guide to Fiordland, writing: ‘out on [Milford] sound itself, beneath the flanks of The Lion or under the towering cliffs of Mitre Peak, time itself speaks loudest of all; waterfalls, forest, mountains and sea, all leave us humbled and hushed by what we have felt and seen.’2 Yet, much as with the illusory wilderness photograph, in the immediate reverse direction of Turner’s tribute is a frenetic airport from which on some days the drone of aircraft never stops. People are herded from their cars past carefully pruned native plants (so as not to block the view), along a boardwalk made from hardwood sourced from somewhere in Asia, and onto diesel-engine boats for a tour during which the boat intercom is rarely silent. This paradox of wilderness tourism is seldom noticed: Internet searches of ‘Milford Sound’ produce only pictures of an un-peopled Mitre Peak and the fiord.

Of course, ‘true adherents’ of wilderness may not regard Milford Sound as wilderness. Craig Potton calls such places an aberration, and likewise laments the noise from aircraft found around Aoraki Mount Cook.3 For the devotee, wilderness is found much further away. It is arrived at only by on-foot journeys made into the more remote corners of this country’s conservation lands: epic adventures, solo traverses, dicey crossings, and saturation in turn by rivers, storms and secret hot pools are the means by which wilderness is found.

This almost transcendental sense of purism, along with its innate desire to run headlong ‘Into The Wild’, has wide appeal. Such shamanism, the roots of which can be traced back to an ongoing lineage of North American wilderness writers from Thoreau to Snyder, has as its focus the individual’s reverie in nature. Yet this also needs challenging. For, in the process of foregrounding an individual’s mental state, it ignores – again like the wilderness photograph – the practicalities of being there. Though people lost in the wild might imagine themselves to be remote from the trappings of civilisation, such a mindset is also illusory.

For instance, on one week-long solo trip from the Cascade River to the Beans Burn via the Red Hills, I stopped for a rest day, pretty much three days’ walk from the nearest track. At my camp I thought to write down the gear I had with me. As well as the more obvious stuff – tent, sleeping bag, parka, pack, cooker and so on – my list included my camera’s memory stick made in Taiwan (and coded AC43-5120- 0182P04B0052), a watch bought at Los Angeles airport, disposable lighters made in France, a big black garden bag bought at Countdown as my pack liner, my credit card, foil sachets of Sweet Thai Chilli Tuna, couscous grown who knows where, a blue Chinese-made sun hat, and a Pilot Green Hi Tecpoint V5 Extra Fine Pen with which I wrote the list. The list grew to over two hundred articles.

So, while looking around I could imagine myself far from anywhere – in one of this country’s more remote stretches of wilderness, where helicopter access is restricted and the traces of people are few – nevertheless the extraordinary array of equipment I carried reinforced a sense of my being removed from, rather than assimilated into, wilderness. The artefacts, with their provenance, production and branding, connected me to places all around the world. Thomas Campanella writes of this contradiction, ‘today our efforts to simplify our lives by snuggling close to nature seem, paradoxically, to require the material of a small army: global positioning systems, Kryptonite flashlights, polyethylene underpants, Gore-Tex outerwear, and satellite phones’.4 With such equipment, wilderness is expected to provide very little. Like landing on the moon, everything necessary for survival is brought, with little if anything gathered there.

What is troubling about this emphasis on self-reliance is how it mutes the capacity of wilderness to involve us in its world. Instead, the purpose of equipment is to insulate: as one outdoor brand states,

to protect you from the elements of nature – to keep you dry, comfortable and safe – out of direct exposure to rain, snow, sun, wind, insects and even animals … [Our tents] grant us the freedom to explore remote wilderness areas independently.5

Wilderness, and by inference our most ecologically indigenous places, is here reduced to a test bed for ‘new toys for the outdoor adventurer’ (as one magazine headed up its new products page). Instead of immersing us in wilderness, such equipment limits nature to being just a backdrop to a person’s conversation with technology.

This sense of being an alien in our own land shapes DOC’s management policies. The Department’s overarching ‘Visitor Strategy’ terms all people in our public conservation lands as visitors. Such a term is all encompassing, including as it does ‘people using visitor centres and clients of concessionaires, New Zealand and international visitors’.6

Applying this logic, the Department declares that visitors ‘are welcomed as valued guests’, and that ‘many New Zealand visitors believe that the opportunity to freely visit these areas is synonymous with the indigenous character of New Zealand’.7 Introducing a discussion on traditional perspectives on access, the ‘Visitor Strategy’ outlines how ‘the special relationship of tangata whenua to the land, to Papatuanuku, influenced the ways in which Māori people visited and used these places.’8

It is highly problematic to discuss issues of belonging and cultural indigeneity through concepts of visiting, particularly when the scale of these conservation lands is considered. Thankfully, the ‘Visitor Strategy’ is now under review, yet a semantic disciplining of the term will only go so far. The Department’s understanding of their role as external managers, and the public’s similar role as external visitors, is more than just an issue of terminology: it pervades the way in which facilities are built and the materials used.

In recent years, partly in response to the Cave Creek tragedy, DOC has adopted a range of design standards for facilities, one of which is the Tracks and Outdoor Visitor Structures Standard SNZ HB8630:2004. The Standard requirements for the seven specific categories of visitor – ‘short stop traveller’, ‘day visitor’, ‘overnighter’, ‘back country comfort seeker’, ‘back country adventurer’, ‘remoteness seeker’ and ‘thrill seeker’ – are organised into specific outcomes. For example, on walks suited to ‘back country comfort seekers’, minimum size specifications are set: for stairs 600 mm, boardwalks 600 mm, and trails 300 mm. These specifications are then broken down further: a stair’s minimum tread depth is 250 mm, the maximum step height 200 mm, and the maximum vertical rise before a landing is required is four metres. Similarly, trails may have only so much mud (it must not come over a boot), and occur for no more than 40 per cent of the track’s length.

These have become the default set of dimensions with which tracks are made and maintained. Such dimensions do not speak of wilderness or the physical landscapes they occupy. Rather, they are based on pre-determined dimensions imposed on sites regardless of the topographical intricacies. There is a growing conformity of design right across the conservation estate: tracks, boardwalks, steps and bridges are increasingly identical. Like the hiker’s equipment, these tracks seek little from the landscapes in which they are installed, treating their environment as little more than a stage for such facilities.

This desire to adhere to single standards is also found in the prescribed track gradients for New Zealand’s most popular walks. While gentle sloping country is readily accommodated, most terrains are more problematic, requiring intrusive modifications. Hence, in the Matukituki Valley, roading contractors with explosives and heavy diggers were called in to excavate the track to Pearl Flat. On such a track, many a person travelling through the forest gains little more than a visual appreciation of the surrounding endemic flora. The ambivalent relationship that such tracks create with conservation lands is one in which wilderness lies – both in its physical form and its experience – beyond both the track and the person.9

The uniform orange triangle track marker, like the signage found across conservation lands, works in the same way. Each marker shows the way through the forest while revealing nothing about the trees on which they are nailed. Instead of reflecting environmental diversity, branding rules – not unlike those adopted by fast food companies – treat the length and breadth of this country identically. This metronomic propensity is also found in recent hut construction and bridge design. It is in no way notable that on the newly completed Motatapu Track the three huts are identical.

While a sameness of facilities may be expected around transit zones such as airports, these uniform solutions are a strange and revealing expression of how we understand our place in this land. Despite ardent fascination and fondness for wilderness, we seem unwilling to let the forms of our equipment, boardwalks, paths, markers and huts evolve out of the environments in which they are placed. Generic solutions are superimposed over, rather than drawn from, the land.

Nor do we find this incongruous. To many of us, these facilities are insignificant tools by which wilderness is travelled to, watched, visited. The type of wilderness they create, like the researchers’ maps, wilderness landscape photographs, and technologically advanced equipment, is one ever located beyond humanity. And it is this ever-present separation that hinders people from becoming a more integral part of the ecologically indigenous qualities of this country.

the middle wilderness

Geoff Park wrote of this division that splits New Zealand into two distinct landscapes. One is a landscape so transformed that native species are almost entirely absent, while another – primarily our public conservation lands – is ‘devoid of humans … Our terra nullius, no less’.10 It was this disjunction between the two that led Park to seek out those ‘middle landscapes’ where opportunities to ‘smudge the boundaries’ could be found.11 Simplistically, we might suppose such ‘middle landscapes’ exist along the boundaries between these two distinct New Zealands: for instance, along the borders of our public conservation lands. Yet ‘middle landscapes’ occur elsewhere: wherever people and the indigenous land interact. In other words, where people and their environment meet: for instance, as the foot walks the ground, as a boardwalk follows a river’s edge, as the hut becomes its surroundings, and so on. Or, as I will now discuss, in the way we cook a meal.

These days, the use of portable cookers is almost universal. They are convenient, light, quick to use, and recognised as being more environmentally friendly than a fire. This is why current best practice, as advocated by the New Zealand Mountain Safety Council, is to use fires only in emergencies. As DOC states in a discussion of ways to ‘minimis[e] your impact’:

the use of fires for cooking, warmth or atmosphere has environmental consequences. Fires use up wood, destroy insects and other animal life, and they can scar sites with blackened and charred fire-places. Fallen wood, especially larger branches and logs, is the source of food and shelter for many forest insects and plants.12

And yet, while the scarring that comes from a poorly sited open fire should certainly be strongly discouraged, is using native timber as a fuel – such as in the form of twigs and branches – similarly unsustainable? Take, for example, a portable twig stove. Similar in function to the Thermette and the Kelty Stove, twig stoves are fashioned from cans in a way that keeps the heat of the fire off the ground. Instead of using white spirits or butane, it is fuelled from the dry wood found around a campsite. In some ways the fuels used for the different stoves are similar: both burn carbon from ancient forests, though the butane/white spirits version uses the produce of ancient forests made extinct many million years ago. The twig stove burns unsequestered carbon from still living ancient forests. In terms of sustainability and climate change, a strong case for using twigs over petroleum can be made.

But sustainability is only one aspect of the issue here. For it is the type of relationship that a fossil-fuelled cooker directs the user to have with a wilderness environment that is so limiting. By requiring less of the place in which it is used, such cookers in their way contribute to relegating the role of wilderness to being merely a setting for ever more sophisticated examples of technology. The purpose of such equipment is not to elicit a more intimate knowing of place. It is about achieving technological superiority in terms of heat output, fuel efficiency, burn- time, field-repair-ability, durability, cost, weight and ease of operation.

In this regard, the twig stove is different. The skill in using it is progressively learnt in the places in which it is used, and not in the store from which it was bought. And through the process of finding fuel from the forest, a more intimate knowing of a specific place is created.

Anthropologists Tim Ingold and Terhi Kurttila describe how this process of becoming knowledgeable about specific places derives from the activities undertaken there. Different types of activities draw out different qualities. It is partly through such processes that places become distinctive. Belonging, they assert, ‘has its source in the very activities, of inhabiting the land, that both bring places into being and constitute persons as of those places, as local’.13 An intimate knowing of wilderness does not come from working out what wilderness might mean – our actions being the direct expression of an already is – but rather what we do in such places.14

Further, Ingold and Kurttila consider that a specific sense of ‘localness’ is determined by the types of technologies used in a location. In the example they use – of travelling in the Lapland wilds – a sense of snow is arrived at ‘in terms of how it affects the performance of their vehicles’.15 A different sense of the same stretch of snow comes through other modes of travel. When walking, ease of movement is impeded if the snow’s crust cannot support a person’s weight where it is concentrated around the boots. Yet, by strapping the same boots into skis, a person’s weight is better distributed so that he or she can glide. In this way, what we know about a specific place is learnt through the interplay of actions, technologies and environment.

In this vein, the elevated boardwalk, the bulldozed valley track, the identically prefabricated hut, the generic track marker, even the equipment that we bring with us into wilderness, all script a performance of people as visitors and aliens in our public lands and waters. Wilderness has come to mean something different from what it might were facilities and activities pursued that sought out a more localised involvement with our ecologically indigenous places. Our current relationship with conservation lands is being shaped by an increasing number of facilities and technologies whose function is to mute the environment’s capacity to routinely direct our actions. We have blunted the capacity for place to challenge and influence who we are.

Path-making

The ways in which acting differently might change our understanding of our public conservation lands can be glimpsed in the simple example of cooking a meal. Yet such an example is based on an individual’s actions in wilderness. It also concerns only one aspect of our outdoor experiences. What of a more collective, and in terms of scope, substantive shift in the way in which we engage with conservation lands?

Consider Ulva Island in Rakiura National Park. Ulva Island is a small, predator- free island, across which a series of paths and boardwalks have been constructed so that the many visitors, in combination with the high rainfall and boggy nature of the ground, don’t damage the surrounding forest. Rather than the uniform design, however, it is the choice of materials being used on Ulva Island that provides a key insight into our collective attitude. For just as we have institutionalised a mindset of people as outsiders, so also are all the materials used in public conservation lands sourced from beyond it.

DOC’s national standard stipulates that all timber structures – including boardwalks, bridges and viewing platforms – be made exclusively of exotic pinus radiata: a commercially grown plantation timber. The timber used on Ulva Island has been freighted in pre-cut lengths across Foveaux Strait, and grown on lands, most likely in Southland, that less than 150 years ago were themselves native forest. Because fast-growing pinus radiata readily rots, it has to be impregnated with a mix of cadmium, chromium and arsenic to make it durable. A related standard stipulates that treated timbers of the grade used by DOC (H3 and above) must, at the end of their usable life, be buried in a landfill. This means that, for Ulva Island to remain uncontaminated, when the boardwalks become unusable they will need to be disassembled, removed, and buried.

Implicit in this approach is tacit acceptance that polluting technologies are acceptable provided that all impacts are located beyond the borders of our public conservation lands. Yet even this is an illusion, for freshly treated timber is prone to chemical leaching. Working with it on sites such as Ulva Island scatters unrecoverable toxic dust and waste. Furthermore, its transportation to a site – often by helicopter – requires significant quantities of fossil fuels.

This irony is evident in the photograph opposite. Here the present track – defined by the pinus radiata edging – has been routed around a fallen tōtara tree. Notwithstanding the anti-fungal properties of treated pine, it is certain that, were this tōtara to be used for some of the island’s boardwalks, it would outlast any treated pine. Apart from removing the carbon footprint involved in treating and transporting the pinus radiata, by building a track with the tōtara wood, when the native timber finally did rot, the track would assimilate back into the forest from which the wood had grown. Indeed, even during its temporary life as a boardwalk, it would continue to perform its role as an integral part of the island’s distinctive ecological cycles.

If the only concern was which type of timber was both less polluting and more ecologically sustainable, then the use of local native timbers for DOC facilities would be widely accepted. However, it is the threat of a deeper loss that is at stake: for using native timbers degrades a need to perceive this country’s public conservation lands as an untouched first Eden. This Edenic myth has its roots in a collective national guilt for the environmental destruction that, in the 1880s alone, saw forests covering 14 per cent of New Zealand’s land area felled and cleared. Mile after mile of country was ‘lands with fallen timber, stumps blackened by fire, and great trunks standing scarred and broken, with no vestige of green upon them’.16 Nor was that the end of it. Throughout much of the twentieth century, clear-felling of native forests continued.

It is the tacit knowledge of this that leads us to fear that chopping down even one native tree, much like one drink for the reformed alcoholic, could open our collective psyche to another uncontrollable fever of destruction. Perhaps this should remain the case. It may seem that the only way we can support this image of purity – the backbone of our tourism marketing – is to maintain a distance from wild New Zealand.

Detail of Ulva Island Track, Stewart Island. Mick Abbott.

However, to do this is to support a dangerous misconception. For our forests are increasingly silent. Rather than unique birds and fish, it is rodents, stoats, possums, deer, trout and didymo that are rife. Nor are the extinctions that have been associated with people’s arrival to this land over. Habitat loss, the relentless pressure of invasive species, and now climate change continue to modify the make- up of public conservation lands. Left to themselves, the endemic qualities of New Zealand wilderness will dissipate ever faster. Countering such threats requires considerable ongoing funds and effort. This is why, notwithstanding budget cuts, there are significant shifts underway in acknowledging the place of people in public conservation lands. Volunteer programmes are on the increase, and DOC, for a period, has included on business cards and other material, alongside imperatives to ‘protect’ and ‘enjoy’, the call to ‘be involved’. The challenge is to make sure such involvement is two-way.

the generativity of wilderness

The philosopher-geographer Yi Fu Tuan points out that in the nineteenth century it was ‘generativity’ that lay at the heart of wilderness’s capacity to capture North America’s imagination. Out of the wilderness came a social and ecological transformation. Of course in the nineteenth century, both there and in New Zealand, the cost of this was the consumption of wilderness to form settlements, industries and farmland.17 That which was spared was reserved and preserved, rather than irrevocably spent. Nor can we be so naïve as to believe that such threats are past, for in this country there remains a strong cavalier culture of development. A keenness to extract economic value is not matched with a sustainably grounded ambition to ensure environmental and social benefit. Cautionary examples are readily found, as public anxiety over the recent spate of coastal subdivisions and imminent opening up of conservation lands for mining attests.

Yet, the purpose of this essay is to ask if it is possible to reimagine wilderness – and in the New Zealand context, public conservation lands – as something different than either a preserve to be left or a resource to be used. Could wilderness become similarly generative in shaping our sense of who we are and what we do in this land, without the corollary that it must be consumed in the process? While there are certainly risks in allowing such a possibility, other risks arise from inaction. For the status quo firmly constrains us to understanding our native flora and fauna as little more than a curated museum exhibit, the purpose of which is to let the visitor get an aesthetic rush. Nor is it viable to continue understanding what wilderness is – as per the map researchers discussed at the start of this essay – on the basis of what it is not. Instead, we need to be able to identify what wilderness is in terms of people’s roles in fostering, building and creating it: of being involved.

What if public conservation lands were understood as an incubator for exploring sustainable ways to work with ecologically indigenous New Zealand, so that lessons learnt could be applied, not only across conservation lands, but also beyond it? Instead of being a place in which people become expert at handling toxic timber – itself grown through the cloning of exotic species – it might become somewhere in which tōtara, rimu and kauri were planted for localised use by future generations. Native timber species at trailheads and car-parks could replace the plethora of boardwalks, bridges and huts built out of cadmium, chromium and arsenic-treated pine, and the skills of milling a windfall on-site and working a single log into a foot bridge (as is commonplace in North American national parks) re-learnt. Rather than helicoptering in prefabricated huts, shelters might be built that spoke of an intricate knowing of the places in which they are located.

The ‘aberrant’ Piopiotahi Milford Sound could become a hothouse of innovative ideas and activities, dedicated to ‘treading lightly’ on the land. Imagine the cameras of international tourists being drawn as much to the way we are in these places as to the landscapes we are so fortunate to live with. The list could go on: from popular destinations like Milford Sound being serviced by hop-on hop-off light electric rail, to a national park’s operations being carbon neutral (without recourse to offsetting), and to using volunteer labour to fill gabion baskets with nearby river stones as a means to build a hut’s foundations and walls.

The ideas suggested here are not intended to be definitive. The goal is not to produce some archetypal national park. When we celebrate this land’s ecological diversity, we ought to do so in ways that reflect and support our cultural diverseness. To this end, we should be happy to explore in different places and communities alternative ways of being involved: for instance, experimenting on the Milford Track with cradle-to-cradle sewerage systems rather than allowing the extensive use of carbon-polluting helicopters to fly out human waste, continuing the heritage of quirky huts in Kahurangi National Park, trialing localised signage around Arthur’s Pass National Park, maintaining a Great Walk without the use of motorised machines (as occurs on the Appalachian trail), developing popular corridors like the Milford Road as a carbon-neutral route.

The potential of this engagement can be developed even further. It was as much the braided nature of Canterbury’s wild rivers as the inventing skills of Bill Hamilton that produced the Hamilton Jet. Its innovation was a direct response to an environment that had always belonged here. This country’s reputation for quality outdoor gear and clothing arose from a similar engagement. Rather than being the product of clever design, its durability and clever features have come directly from the regular and close relationship many people have with this country’s rugged mountains and forests. Only in Aotearoa New Zealand is a third of the land area public conservation land. What’s also rare is its accessibility. Such qualities not only make this country distinctive, but so also who we are as people, and the things we might produce. It is in our ongoing relationship with this country’s public conservation lands, and not one-off returns from minerals, where enduring economic and social value is most likely to be found. It is the uniqueness of this place that makes both us unique, and with it – should we choose – the products, services and experiences we develop and export around the globe.18

The future of this country’s conservation lands does not lie in maintaining them as a preserve in which its people are made to act and think like outsiders. Rather, it lies in working deeply through the complex issues of what it means to tread lightly both within them and so also across all of this country: to act in ways that enable native birds, native plants, indigenous ecosystems, and people all to flourish.

1 J. Shultis, ‘The Duality of Wilderness: Comparing Popular and Political Conceptions of Wilderness in New Zealand’ in G. Cessford, ed., The State of Wilderness in New Zealand, pp. 59–73. Wellington: DOC, 2001.

2 B. Turner and M. De Hamel, The Visitor’s Guide to Fiordland New Zealand, Te Anau: New Zealand National Travel Association, Fiordland Branch, 1983, p. 23.

3 R. Cullen, J. Harland, C. Potton & New Zealand Tourism Policy Group, ‘Collection of Essays on Equity and Access to Natural Areas’, Wellington: Tourism Policy Group, Ministry of Commerce, 1994, p. 9.

4 T. Campanella, ‘The Rugged Steed’, Harvard Design Magazine, vol. 10, 1997, p. 63.

5 Fairydown Clothing and Equipment Product Catalogue, Christchurch: Arthur Ellis & Co, 2000, p. 26.

6 DOC & New Zealand Conservation Authority, ‘Visitor Strategy’, Wellington: DOC, 1995, p. 2.

7 Ibid., p. 10.

8 Ibid., p. 3.

9 See M. Abbott, ‘Being Landscape’ in Making Our Place, Dunedin: Otago University Press, 2011.

10 G. Park, ‘Our Terra Nullius’, Landfall 204 (2002): 65.

11 G. Park, Theatre Country: Essays on Landscape & Whenua, Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2006, p. 206.

12 DOC. ‘Plan and Prepare: Minimising your impact. Take care with stoves and fires’, www.doc.govt.nz/templates/page. aspx?id=38536 (accessed 23 March 2008).

13 T. Ingold & T. Kurttila, ‘Perceiving the Environment in Finnish Lapland’, Body & Society, vol. 6, no. 3/4, 2000, p. 185.

14 See M. Abbott, ‘Being Landscape’, in Making Our Place: Exploring Land-Use Tensions in Aotearoa New Zealand, edsJ. Ruru, J. Stephenson and M. Abbott, Dunedin: Otago University Press, 2011.

15 Ibid., p. 188.

16 Mrs Robert Wilson, In the Land of the Tui: My Journal in New Zealand (1894), quoted in Geoff Park, Theatre Country: Essays on Landscape and Whenua, Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2006, p. 212.

17 Y. Tuan, Foreword, in K. Olwig, ed., Landscape, Nature, and the Body Politic: From Britain’s Renaissance to America’s New World, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2002, pp. xi–xx.

18 See, for example, iPhone and iPad applications and other products being developed with the Department of Conservation by Scope DesignLab at the University of Otago.